How to generate good will in your organisation, or not: An Introduction to the good-will/ill-will Invertible Dynamic (The good-will/ill-will flip)

Setting the stage

Is it contestable that, as human beings, we are a ‘work in progress’? Humans eh! Cant live with them: cant live without them. That’s probably a sentiment that resonates with most people on this beautiful blue planet. It seems we can swing from creating and celebrating the greatest achievements and moments of culture to trying to wipe each other off the face of the earth, with relative ease.

So what prompts this rather fickle about-face? That is an issue I wish to explore in this short essay. I intend to focus on the way we work together in an organisational setting but I believe the principle is applicable to all situations where humans interact with each other, including the way we interact with our own inner-selves.

Most of us are very messy, and bring lots of ‘stuff’ with us into the workplace, the vast majority of which is never formally acknowledged or directly addressed, except possibly at a disciplinary hearing, (Masters Builders) or when we have some form of personal breakdown. In addition we often have unacknowledged agendas and different motives for doing the job in the first place, and often these are very personal, with the result that we often cut across each other with differing visions of what it is we have agreed to do together..

In most organisations focus and direction is provided and clearly defined by managers. A clear chain of command can, to some extent, override and control the various agendas of those lower down in the organisation.

Is it contestable that, as human beings, we are a ‘work in progress’? Humans eh! Cant live with them: cant live without them. That’s probably a sentiment that resonates with most people on this beautiful blue planet. It seems we can swing from creating and celebrating the greatest achievements and moments of culture to trying to wipe each other off the face of the earth, with relative ease.

So what prompts this rather fickle about-face? That is an issue I wish to explore in this short essay. I intend to focus on the way we work together in an organisational setting but I believe the principle is applicable to all situations where humans interact with each other, including the way we interact with our own inner-selves.

Most of us are very messy, and bring lots of ‘stuff’ with us into the workplace, the vast majority of which is never formally acknowledged or directly addressed, except possibly at a disciplinary hearing, (Masters Builders) or when we have some form of personal breakdown. In addition we often have unacknowledged agendas and different motives for doing the job in the first place, and often these are very personal, with the result that we often cut across each other with differing visions of what it is we have agreed to do together..

In most organisations focus and direction is provided and clearly defined by managers. A clear chain of command can, to some extent, override and control the various agendas of those lower down in the organisation.

Stuff happens and how we attempt to control it

And whilst ‘stuff’ happens wherever human beings come together, there is something about the restraining influence of a hierarchical organisation that seems to hold things in check in a way that doesn’t necessarily happen in a more open initiative.

Social hierarchies, by their very nature seek to channel human behaviour into certain pre-determined directions. (Allen) It becomes hard to take initiative because, to a large extent, the initiative has already been taken. We don’t make up the social rules because they have usually already been set in stone and codified before we arrive on the scene.

From the perspective of the organisations world-outlook it is often difficult to tell the difference between an action that is ‘merely’ dysfunctional and destructive and one that is creative and innovative as neither types of action are likely to conform to the pre-set structure of the organisation, or group. The same pre-set rules and regulations therefore serve to restrict both creative and dysfunctional behaviour.

And whilst ‘stuff’ happens wherever human beings come together, there is something about the restraining influence of a hierarchical organisation that seems to hold things in check in a way that doesn’t necessarily happen in a more open initiative.

Social hierarchies, by their very nature seek to channel human behaviour into certain pre-determined directions. (Allen) It becomes hard to take initiative because, to a large extent, the initiative has already been taken. We don’t make up the social rules because they have usually already been set in stone and codified before we arrive on the scene.

From the perspective of the organisations world-outlook it is often difficult to tell the difference between an action that is ‘merely’ dysfunctional and destructive and one that is creative and innovative as neither types of action are likely to conform to the pre-set structure of the organisation, or group. The same pre-set rules and regulations therefore serve to restrict both creative and dysfunctional behaviour.

The rise of the grass-roots social organisation

Within the last 100 years, and with increasing frequency, a raft of new social groups have emerged to fight, campaign, champion and preserve what we might loosely describe as the human commons, whether this be in the form of environmental preservation; initiatives in establishing and maintaining universal human rights; or simply exploring innovative new ways to think, live and believe.

Collectively we can classify this emerging sector as the Third, or Community Sector. Globally the emergence of such initiatives now runs into the hundreds of thousands and seems to be accelerating as the number of ‘fractures’ in the existing socio-economic ‘models’ multiply.

Within the last 100 years, and with increasing frequency, a raft of new social groups have emerged to fight, campaign, champion and preserve what we might loosely describe as the human commons, whether this be in the form of environmental preservation; initiatives in establishing and maintaining universal human rights; or simply exploring innovative new ways to think, live and believe.

Collectively we can classify this emerging sector as the Third, or Community Sector. Globally the emergence of such initiatives now runs into the hundreds of thousands and seems to be accelerating as the number of ‘fractures’ in the existing socio-economic ‘models’ multiply.

|

These social initiatives generally aspire to be inclusive of all members, to optimise their input with little or no hierarchy and also to recognise the intrinsic ‘right’ of the individuals within its ‘ranks’ (sic) to explore and achieve their own intrinsic sense of meaning and fulfillment.

One would expect such initiatives therefore to be less riven by conflict and strife than the allegedly dysfunctional ‘old-style’ hierarchical operations that they seek to reform or replace. But that is not my experience. |

|

So many good intentions: so many failures

My experience is that such initiatives make a number of ‘fatal’ mistakes, which I will elaborate on in further essays. Suffice to say that the general pattern of these initiatives seems to be that, after an often exuberant and exhilarating start, in which much energy is expended, said initiatives start to get stuck when they begin to address the inevitable complexity of actually achieving and maintaining, over time, the objectives and ‘new’ social forms they initially set out to create.

The result is they either collapse relatively early in their organisational ‘life’ or they gradually (or suddenly) adopt a more traditional hierarchical form of working, with all the attendant restrictions on human initiative mentioned above.

My experience is that such initiatives make a number of ‘fatal’ mistakes, which I will elaborate on in further essays. Suffice to say that the general pattern of these initiatives seems to be that, after an often exuberant and exhilarating start, in which much energy is expended, said initiatives start to get stuck when they begin to address the inevitable complexity of actually achieving and maintaining, over time, the objectives and ‘new’ social forms they initially set out to create.

The result is they either collapse relatively early in their organisational ‘life’ or they gradually (or suddenly) adopt a more traditional hierarchical form of working, with all the attendant restrictions on human initiative mentioned above.

The magic key

Is there a key to organisational reform that will both help new initiatives to ‘stabilise’ and ‘old’, existing ogranisations and social structures, to renew themselves? I believe there is and I believe it can be summed up quite succinctly in the form of a simple interpersonal (and intra-personal) mechanism.

I call this mechanism the Good-will/Ill-will Invertible Dynamic, or good will/ill will flip, for short.

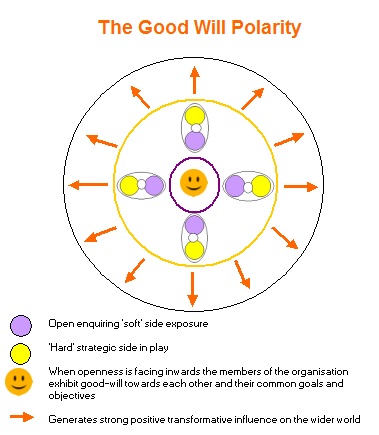

Although it might sound rather obvious, I discovered that a key ingredient for any effective team working is good will. It seems that if we are personally inspired to work towards achieving a particular goal, whilst we believe and feel that our colleagues are also working towards the same goal, and that we are included in this process, it generates good will.

Is there a key to organisational reform that will both help new initiatives to ‘stabilise’ and ‘old’, existing ogranisations and social structures, to renew themselves? I believe there is and I believe it can be summed up quite succinctly in the form of a simple interpersonal (and intra-personal) mechanism.

I call this mechanism the Good-will/Ill-will Invertible Dynamic, or good will/ill will flip, for short.

Although it might sound rather obvious, I discovered that a key ingredient for any effective team working is good will. It seems that if we are personally inspired to work towards achieving a particular goal, whilst we believe and feel that our colleagues are also working towards the same goal, and that we are included in this process, it generates good will.

Re-building the commons or repeating its tragedy

We feel more secure and held by the situation and will be more prepared to listen to the points of view of others. We will also take more responsibility for regulating our own inner anxieties and potential ‘anti-social’ behaviour, in order to contribute to the common good.

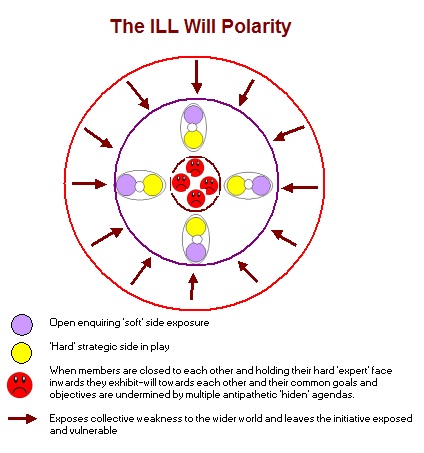

If, on the other hand, we no longer feel supported, accepted or understood, and feel excluded, we begin to question why we are making such an effort and we begin to rein in our good will and go on the defensive and, in the process, often initiative actions that run counter to the stated objectives of the group.

During my work with various organisations, over the years, I discovered that, for those circumstances to arise, a blame culture of recrimination and buck passing is needed. And that, along with an increasing pressure to conform, goes an increasing tendency to find creative ways of avoiding conformity.

We feel more secure and held by the situation and will be more prepared to listen to the points of view of others. We will also take more responsibility for regulating our own inner anxieties and potential ‘anti-social’ behaviour, in order to contribute to the common good.

If, on the other hand, we no longer feel supported, accepted or understood, and feel excluded, we begin to question why we are making such an effort and we begin to rein in our good will and go on the defensive and, in the process, often initiative actions that run counter to the stated objectives of the group.

During my work with various organisations, over the years, I discovered that, for those circumstances to arise, a blame culture of recrimination and buck passing is needed. And that, along with an increasing pressure to conform, goes an increasing tendency to find creative ways of avoiding conformity.

The personal dimension

At any given time we have, embodied within our persona, various strengths and weaknesses. If we want to get a job done we use our experience, in the form of strengths and capacities, to get the job done, and it is a ‘simple’ matter of working out what needs doing, who is best suited to doing it, and getting it done: This is a typical meritocratic way of working, probably best exemplified in academic communities.

However, when it comes to our weaknesses, inadequacies and anxieties we like to keep these covered, even though we would often like to deal with them. But we are only prepared to do so when we feel safe. A common denominator of all Person Centred counselling is the understanding that these ‘personal flaws and inconsistencies’ represent our growth potential; the raw material which, if more deeply self-understood, would allow us to be more of who we are and therefore help us to make a stronger contribution to the task in hand.

At any given time we have, embodied within our persona, various strengths and weaknesses. If we want to get a job done we use our experience, in the form of strengths and capacities, to get the job done, and it is a ‘simple’ matter of working out what needs doing, who is best suited to doing it, and getting it done: This is a typical meritocratic way of working, probably best exemplified in academic communities.

However, when it comes to our weaknesses, inadequacies and anxieties we like to keep these covered, even though we would often like to deal with them. But we are only prepared to do so when we feel safe. A common denominator of all Person Centred counselling is the understanding that these ‘personal flaws and inconsistencies’ represent our growth potential; the raw material which, if more deeply self-understood, would allow us to be more of who we are and therefore help us to make a stronger contribution to the task in hand.

Where is my true mirror?

However, the irony is that we invariably need others to serve as ‘constructive reflectors’ so that we can see our own tail, so to speak. Such persons (or if we leave it long enough “life itself”) need to be conscious enough to detach themselves from the ‘game’ of action and reaction we are embroiled in (Berne) whilst still remaining sympathetic to our situation.

For such a therapeutic approach to be effective in an in-situ real world group setting all members of the group need to recognise and be able to adopt the role of constructive reflectors.

In order to expose my weaknesses within a group setting I need to trust that when I tell you what I am not good at, or what I have failed at, you are not going to use that information against me. If there is good will between us I am more likely to reveal my weak points – the ones that need attention, and we can work out a professional response or self development/training programme accordingly.

If, on the other hand, we operate in a blame culture I am going to hide my flaws and weaknesses from you and put on my character armour. (Reich). The cooperative workplace is then transformed into an emotional and psychic battleground. And the collective workload increases, as our creativity is re-directed to finding effective ways of covering our backs and passing the buck.

However, the irony is that we invariably need others to serve as ‘constructive reflectors’ so that we can see our own tail, so to speak. Such persons (or if we leave it long enough “life itself”) need to be conscious enough to detach themselves from the ‘game’ of action and reaction we are embroiled in (Berne) whilst still remaining sympathetic to our situation.

For such a therapeutic approach to be effective in an in-situ real world group setting all members of the group need to recognise and be able to adopt the role of constructive reflectors.

In order to expose my weaknesses within a group setting I need to trust that when I tell you what I am not good at, or what I have failed at, you are not going to use that information against me. If there is good will between us I am more likely to reveal my weak points – the ones that need attention, and we can work out a professional response or self development/training programme accordingly.

If, on the other hand, we operate in a blame culture I am going to hide my flaws and weaknesses from you and put on my character armour. (Reich). The cooperative workplace is then transformed into an emotional and psychic battleground. And the collective workload increases, as our creativity is re-directed to finding effective ways of covering our backs and passing the buck.

Summing up

The Good-will / Ill-will Invertible Dynamic can therefore be summed up in the following simple formulations:

1) Work will be spent creatively in order to achieve the agreed-shared aims of the group or organisation or to subtly or overtly undermine it according to the amount of collective and individual good-will or ill-will present amongst the organisations members.

2) An inner flip from one state to the other is triggered by any incident that either increases the individual’s sense of belonging, and therefore security, or their sense of isolation and therefore danger.

3) Such a flip is instantaneous and results in an inner intention that leads to a change in behaviour, itself triggered by the change in attitude.

4) The effects of this change may take a long time to manifest, or they may be instantly noticed.

5) When action is motivated by good-will the actions of the group make the organisation, and its effect on the wider world, strong, whilst members are more likely to share their weaknesses, anxieties and failings with their colleagues on the protective ‘inside’ of the organisation.

6) When action is motivated by ill-will the actions of the group make the organisation weak and expose it to outer attack, or erosion, whilst the members strengths are used within the organisation to protect themselves from each other.

7) This is because, in the good will situation the work that is addressed is that which conforms with the fulfillment of the groups aims and because the responsibility for both successes and failures are shared.

8) In the in the ill-will situation, the work that is created is increasingly internal and designed to displace or avoid responsibility for failure being pinned on the groups members. Therefore ‘real’ output drops whilst the output of work designed to move responsibility for action around, increases.

It follows that to the extent that an organisation encourages good will it is likely to have a better chance of achieving is aims and persisting as an entity that is co-incident with its founding objectives for longer.

The Good-will / Ill-will Invertible Dynamic can therefore be summed up in the following simple formulations:

1) Work will be spent creatively in order to achieve the agreed-shared aims of the group or organisation or to subtly or overtly undermine it according to the amount of collective and individual good-will or ill-will present amongst the organisations members.

2) An inner flip from one state to the other is triggered by any incident that either increases the individual’s sense of belonging, and therefore security, or their sense of isolation and therefore danger.

3) Such a flip is instantaneous and results in an inner intention that leads to a change in behaviour, itself triggered by the change in attitude.

4) The effects of this change may take a long time to manifest, or they may be instantly noticed.

5) When action is motivated by good-will the actions of the group make the organisation, and its effect on the wider world, strong, whilst members are more likely to share their weaknesses, anxieties and failings with their colleagues on the protective ‘inside’ of the organisation.

6) When action is motivated by ill-will the actions of the group make the organisation weak and expose it to outer attack, or erosion, whilst the members strengths are used within the organisation to protect themselves from each other.

7) This is because, in the good will situation the work that is addressed is that which conforms with the fulfillment of the groups aims and because the responsibility for both successes and failures are shared.

8) In the in the ill-will situation, the work that is created is increasingly internal and designed to displace or avoid responsibility for failure being pinned on the groups members. Therefore ‘real’ output drops whilst the output of work designed to move responsibility for action around, increases.

It follows that to the extent that an organisation encourages good will it is likely to have a better chance of achieving is aims and persisting as an entity that is co-incident with its founding objectives for longer.

But how to achieve this?

I discovered that having a shared ideal is not enough to really work together effectively in the long term. What is needed is some facility for encouraging ongoing personal development, which is formally supported and assisted by the organisation as part of its ongoing ‘professional development’ program.

Effectively this means that whilst the individual members are putting energy and time into the organisation to assist it in the achievement of its goals, the organisation itself must have ways of putting itself and its resources at the service of the individuals within it, in order to assist them with the achievement of their own personal development goals.

I discovered that having a shared ideal is not enough to really work together effectively in the long term. What is needed is some facility for encouraging ongoing personal development, which is formally supported and assisted by the organisation as part of its ongoing ‘professional development’ program.

Effectively this means that whilst the individual members are putting energy and time into the organisation to assist it in the achievement of its goals, the organisation itself must have ways of putting itself and its resources at the service of the individuals within it, in order to assist them with the achievement of their own personal development goals.

|

And this must not just be in the form of money.

Why is this important? Because, as I stated at the beginning of this article, we are all continually making mistakes, due to our intrinsically unfinished nature. That means that more often than we care to admit and despite our best intentions, or sometimes because we are being deliberately self-centered, we mess things up for others at an interpersonal and group level. |

|

A solution? No blame: no pain

Forgiveness has been an intrinsic element of virtually all social/world-view codes for millennia.

But forgiveness, without understanding amounts to little more than ‘letting people off’. I believe that understanding is the crucial ingredient here. Specifically to understand something of the underlying perspective (world view) and motivation of the other. Essentially to ask “why did you do that? No really. We might learn something that will benefit us if we understand why.” Maybe it will help us all become more self-actualised. (1)

For it is a sad fact of our ‘unfinished state’ that unfortunately most people, including myself, are not so well self-actualised that we can always notice the intrinsic capacity of our colleagues. And there is a lot we can learn from unpacking the motivations and rationale behind behavior that deviates from what we ‘expect’ from ourselves and from others.

A culture that enshrines a genuine attempt to understand when things don’t work out as planned with as little recourse to blame or punitive action as possible is most likely to thrive. After all, is this not what the culture of science and the scientific method itself advocates?

If the delegation of initiative taking is to lead to the development of effective long-term organisational forms we need to find ways of counterbalancing the delegation of initiative taking with an equal take up of personal responsibility for ones actions: a greater internalised sense of self-responsibility couple with a methodology for continually re-assessing the actions and evolving motivations and insights of all players in a way that is at least as efficient as the conventional organisational methodologies.

My own experience has led me to the conclusion that where an organisation seeks to open up its decision making structure, it needs to embed a culture of basic counseling and self-counseling skills into all its members as part of their professional skills.

Forgiveness has been an intrinsic element of virtually all social/world-view codes for millennia.

But forgiveness, without understanding amounts to little more than ‘letting people off’. I believe that understanding is the crucial ingredient here. Specifically to understand something of the underlying perspective (world view) and motivation of the other. Essentially to ask “why did you do that? No really. We might learn something that will benefit us if we understand why.” Maybe it will help us all become more self-actualised. (1)

For it is a sad fact of our ‘unfinished state’ that unfortunately most people, including myself, are not so well self-actualised that we can always notice the intrinsic capacity of our colleagues. And there is a lot we can learn from unpacking the motivations and rationale behind behavior that deviates from what we ‘expect’ from ourselves and from others.

A culture that enshrines a genuine attempt to understand when things don’t work out as planned with as little recourse to blame or punitive action as possible is most likely to thrive. After all, is this not what the culture of science and the scientific method itself advocates?

If the delegation of initiative taking is to lead to the development of effective long-term organisational forms we need to find ways of counterbalancing the delegation of initiative taking with an equal take up of personal responsibility for ones actions: a greater internalised sense of self-responsibility couple with a methodology for continually re-assessing the actions and evolving motivations and insights of all players in a way that is at least as efficient as the conventional organisational methodologies.

My own experience has led me to the conclusion that where an organisation seeks to open up its decision making structure, it needs to embed a culture of basic counseling and self-counseling skills into all its members as part of their professional skills.

|

Ground Rules

I would therefore suggest that all group initiatives would benefit from some degree of implementation of the “core conditions” for effective personal and interpersonal communication as practiced and advocated by Carl Rogers. (ref needed)These are: 1) Practicing unconditional positive regard for others (which does not mean having to agree with everything another thinks, does or believes). 2) Developing a capacity for empathy |

|

3) Practicing non-jugementalism (rushing to issue some punishing edict)

In addition to these I would add that there must be culture of confidentiality for that which is shared between colleagues.

In addition to these I would add that there must be culture of confidentiality for that which is shared between colleagues.

In conclusion

We should recognise that individuals have agendas which go beyond the stated objectives of our organisational aims and objectives and that these additional agendas are not only valid in their own right but should be acknowledged and explored in a non-judgemental way.

We should not rush to castigate or punish members of our group who have ‘failed’ but should seek to understand why they did what they did and be open to the possibility that this understanding will contribute to creating better ways of working in the future. If necessary this should involve the re-assigning of work and roles that most suits both the persons contribution ot the organisation and their own personal self-development.

We should embed the principle of intrinsic personal self-development in everything we do together and recognise that we are all works in progress. Not only will this make it easier for us to learn from our mistakes and inform others, it will also open up the possibility that, as we grow and discover what we didn’t know or expect before, this new source of insight can serve as a true source of innovation and creativity for our organisations and group projects.

Michael Hallam

16 June 2014

We should recognise that individuals have agendas which go beyond the stated objectives of our organisational aims and objectives and that these additional agendas are not only valid in their own right but should be acknowledged and explored in a non-judgemental way.

We should not rush to castigate or punish members of our group who have ‘failed’ but should seek to understand why they did what they did and be open to the possibility that this understanding will contribute to creating better ways of working in the future. If necessary this should involve the re-assigning of work and roles that most suits both the persons contribution ot the organisation and their own personal self-development.

We should embed the principle of intrinsic personal self-development in everything we do together and recognise that we are all works in progress. Not only will this make it easier for us to learn from our mistakes and inform others, it will also open up the possibility that, as we grow and discover what we didn’t know or expect before, this new source of insight can serve as a true source of innovation and creativity for our organisations and group projects.

Michael Hallam

16 June 2014

Concluding Observation

I have recently become aware of a A pioneering study by the social enterprise organisation LOCALITY, conducted in conjunction with Vanguard Consulting, which comprehensively details the effects of initiating an ill-will paradigmn within the provision of public support services. Specifically this report details the mounting costs and work-load of a system that fails to aknowledge the existence of or needs of the individuals within it. Its recommendations closely allign with our own.

Notes (1)

Self-Actualised: Achieve a closer alignment between our innermost desire to express ourselves as we uniquely are with our outer actions and results. (My definition)

References

ALLEN, Timothy F. A Summary of the Principles of Hierarchy Theory, Available at http://www.isss.org/hierarchy.htm (accessed 21 February 2009)

MASTERS BUILDERS, AUSTRALIA: Guidance Note – Workplace Counselling. Available at https://www.masterbuilders.com.au/pdfs/GuidanceNote/Guidance%20Note%20-%20Workplace%20counselling.pdf (accessed 21 February 2009)

ERIC BEARNE: Games People Play: 1964

McLEOD, John: Therapy Today – May 2008: Available at http://www.therapytoday.net/index.php?magId=17&action=viewArticle&articleId=33 (accessed 10 February 2009)

MEARNS & THORNE, Person-Centred Counselling in Action, 3rd ed, 2007, Sage Publications.

Carl Rogers: (Full reference needed)

This article is not yet fully referenced.

Self-Actualised: Achieve a closer alignment between our innermost desire to express ourselves as we uniquely are with our outer actions and results. (My definition)

References

ALLEN, Timothy F. A Summary of the Principles of Hierarchy Theory, Available at http://www.isss.org/hierarchy.htm (accessed 21 February 2009)

MASTERS BUILDERS, AUSTRALIA: Guidance Note – Workplace Counselling. Available at https://www.masterbuilders.com.au/pdfs/GuidanceNote/Guidance%20Note%20-%20Workplace%20counselling.pdf (accessed 21 February 2009)

ERIC BEARNE: Games People Play: 1964

McLEOD, John: Therapy Today – May 2008: Available at http://www.therapytoday.net/index.php?magId=17&action=viewArticle&articleId=33 (accessed 10 February 2009)

MEARNS & THORNE, Person-Centred Counselling in Action, 3rd ed, 2007, Sage Publications.

Carl Rogers: (Full reference needed)

This article is not yet fully referenced.

Additional Content that helps to support the observations and processes outlined in this article.

How to blame less and learn more

Mathew Syed

An excellent piece exploring the inability of a blame culture approach to learn from past systemic mistakes and its tendency to lay the foundations for their repeat.

Mathew Syed

An excellent piece exploring the inability of a blame culture approach to learn from past systemic mistakes and its tendency to lay the foundations for their repeat.